The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin

An opera by Robert Wilson

Music by Alan Lloyd, Igor Demjen, Julie Weber, and Michael Galasso

Texts by Robert Wilson, Cynthia Lubar, Christopher Knowles, and Ann Wilson

Choreography by Andrew de Groat

Performed by Robert Wilson and the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds

Premiered on December 14, 1973 at the Opera House of the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn, New York

The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin was more than 12-hour long opera that incorporated scenes from previous plays, e.g. from The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud (1969) and Deafman Glance (1971), as well as new material. It was previewed in mid-September of 1973 at The New Theater (Det Ny Teater) in Copenhagen, Denmark, and after its premiere in New York was shown four times at the Municipal Theater in Sao Paulo, Brazil - under the title The Life and Times of Dave Clark.

In 1973, Robert Wilson's Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds released an LP with sound excerpts from the production. The following two tracks from the LP feature Christopher Knowles's famous text 'Emily likes the TV' (TIMES) and a music for violin solo, composed and performed by Michael Galasso (STALIN):

“After 12 hours of Robert Wilson’s ‘The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin’ it’s hard to find fast words about what you’ve seen/heard/thought/felt. The idiosyncratic seven-act ‘opera’ is so rich and spectacular, its progress through time so stately and antic, the magic of Wilson’s art so suave and self-contained, the huge cast’s devotion so eloquent, that merely to list the ingredients of any one sequence would exhaust this little column of space….

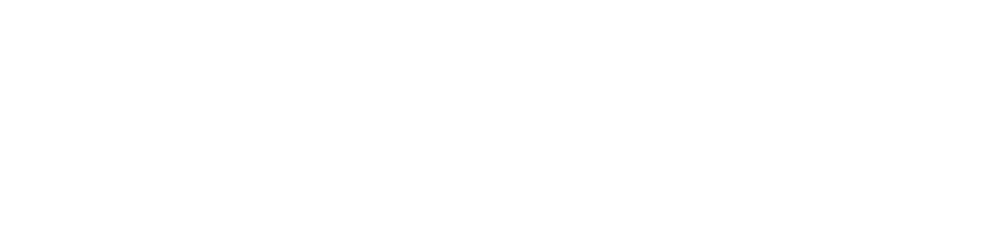

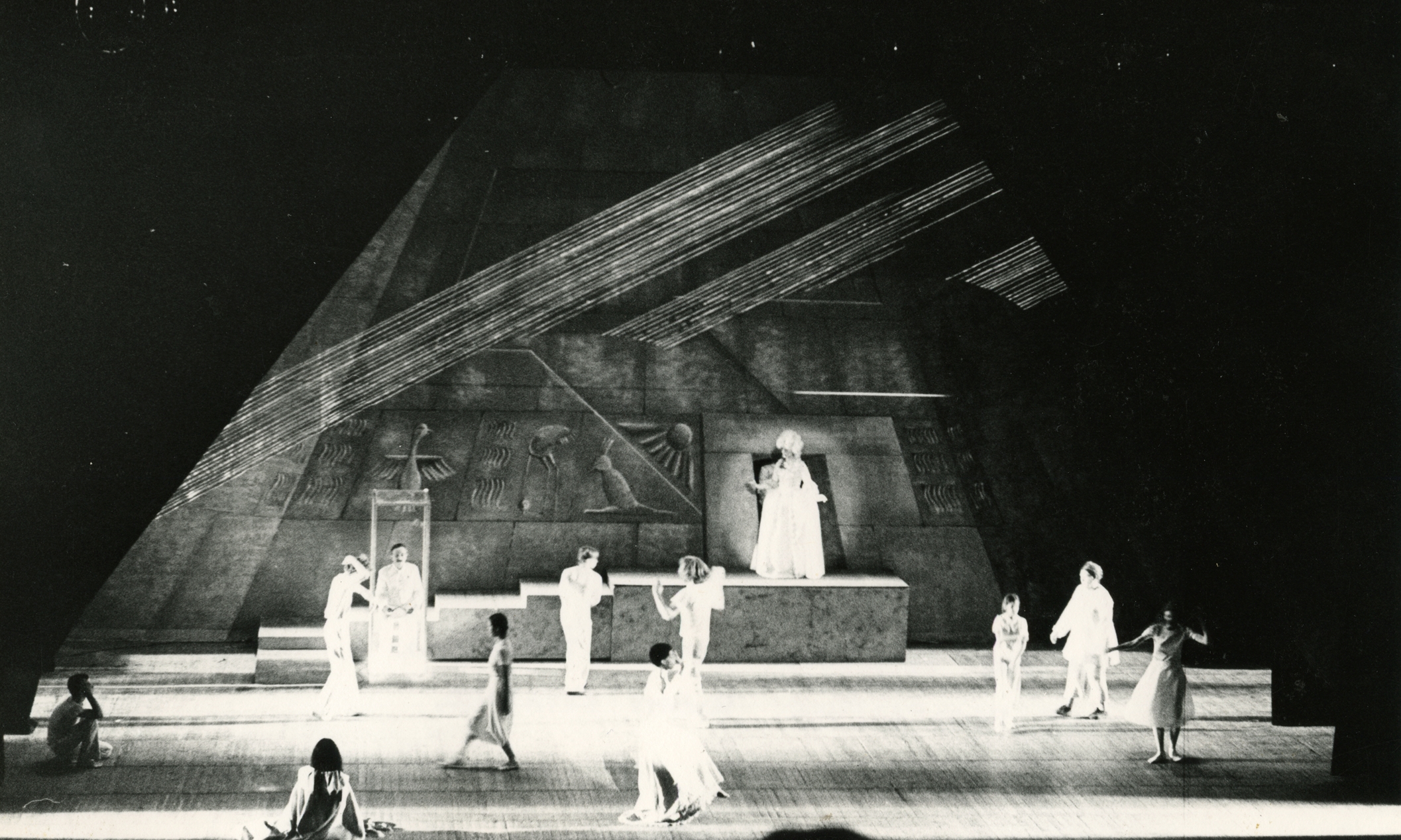

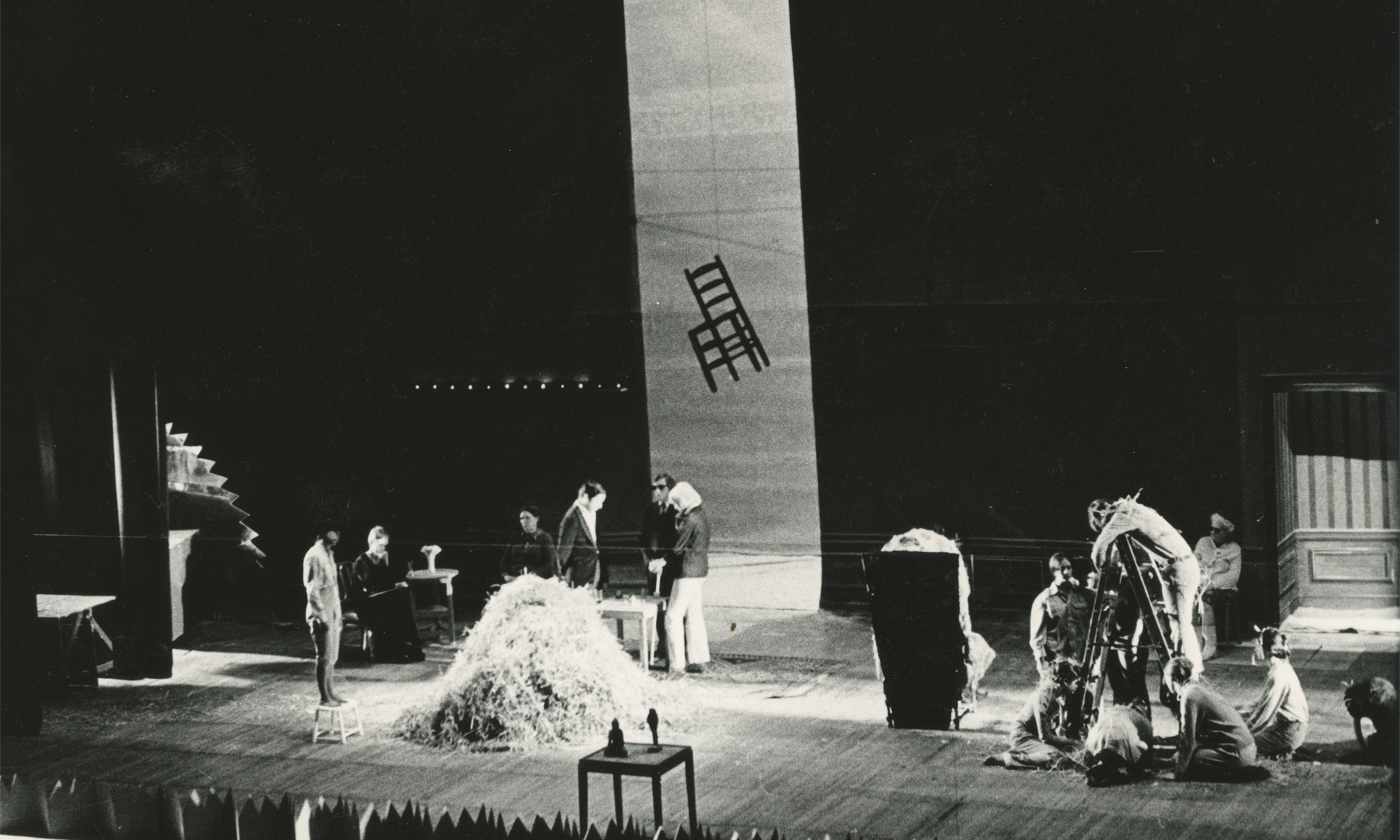

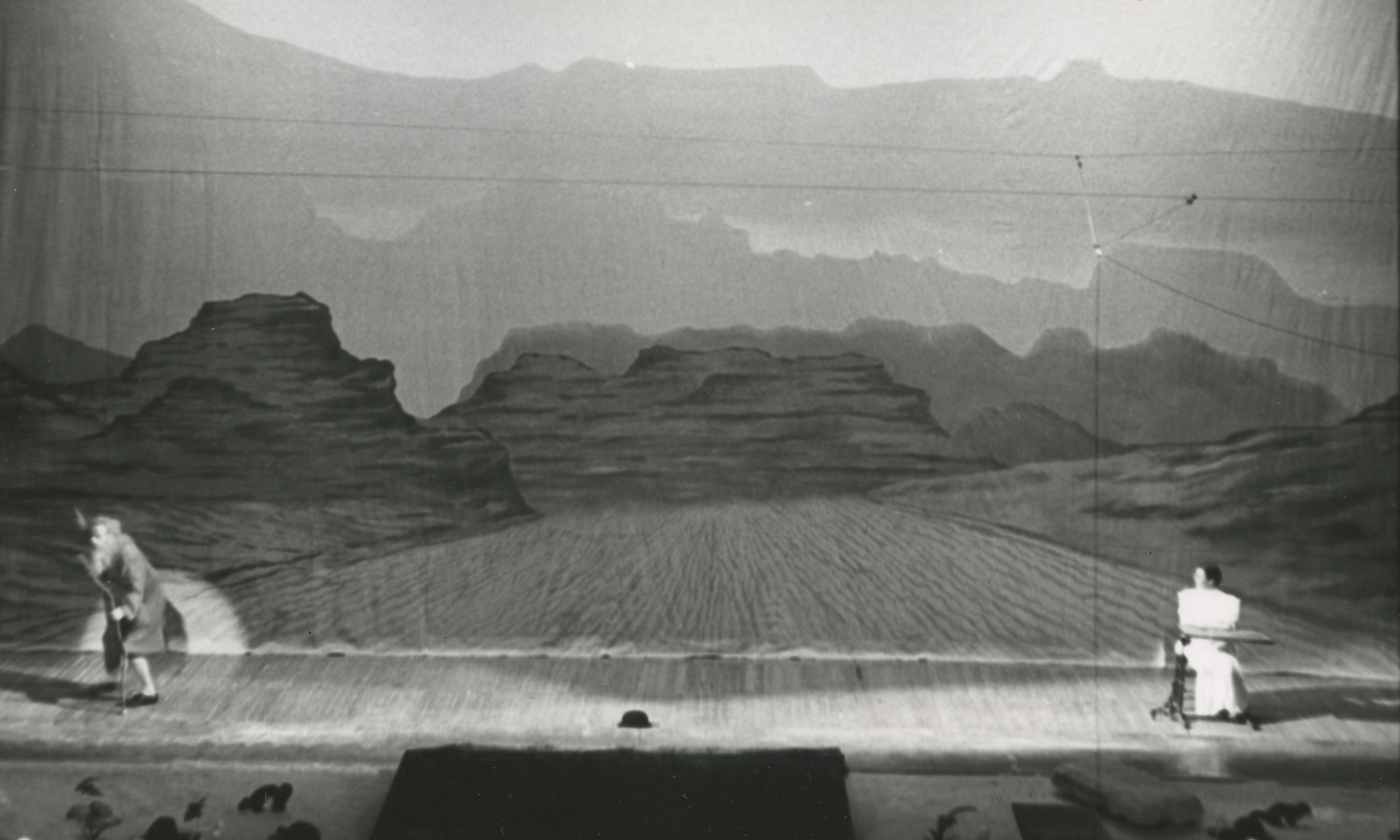

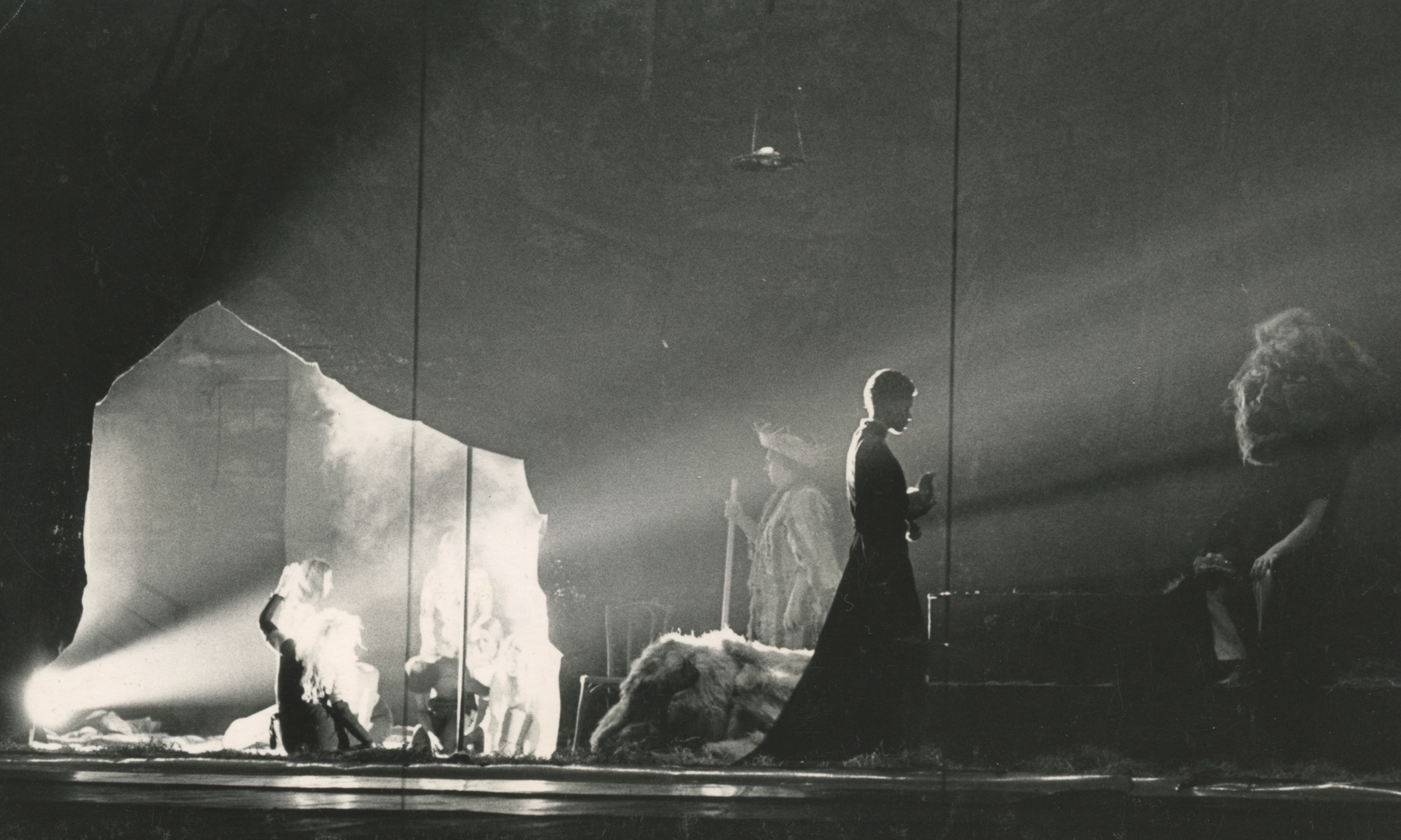

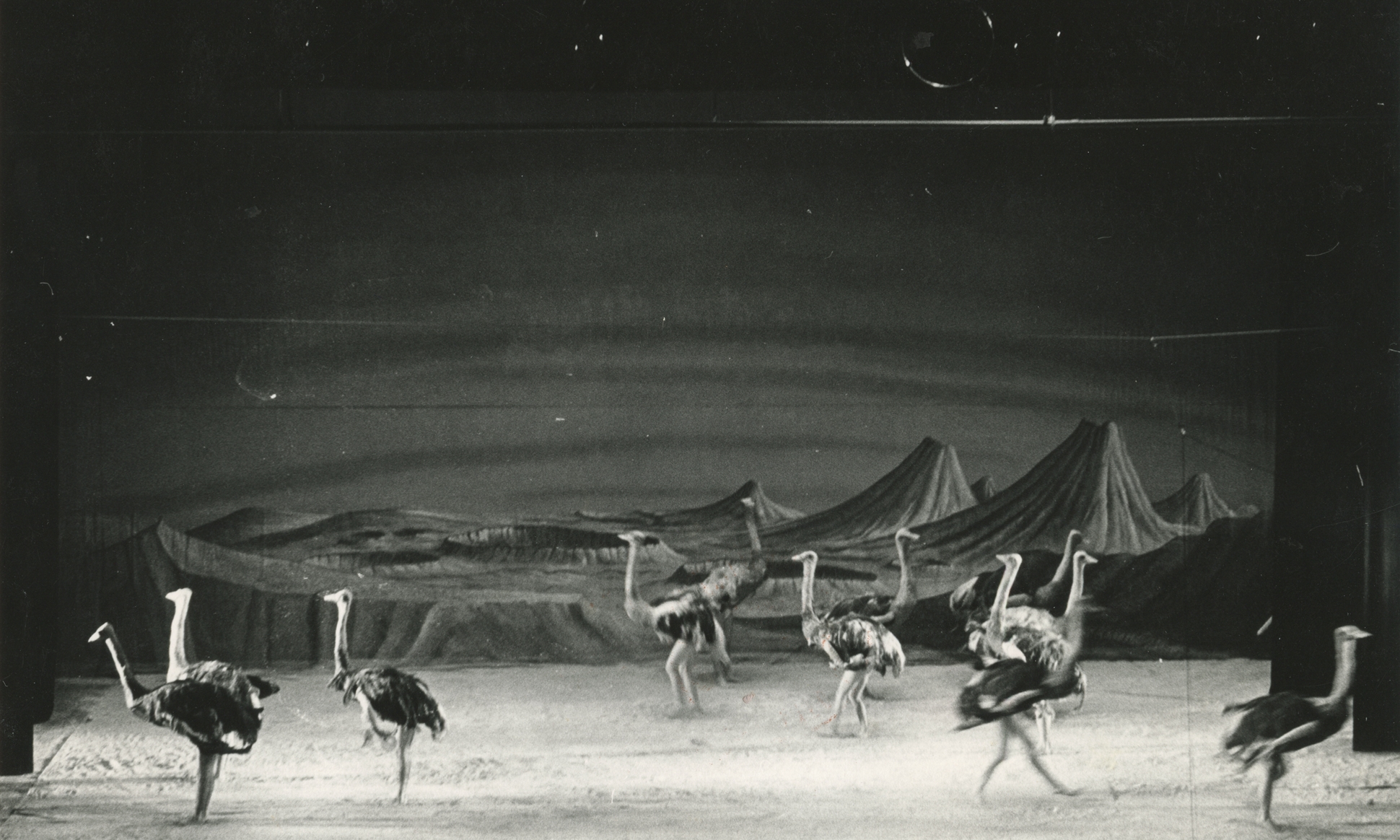

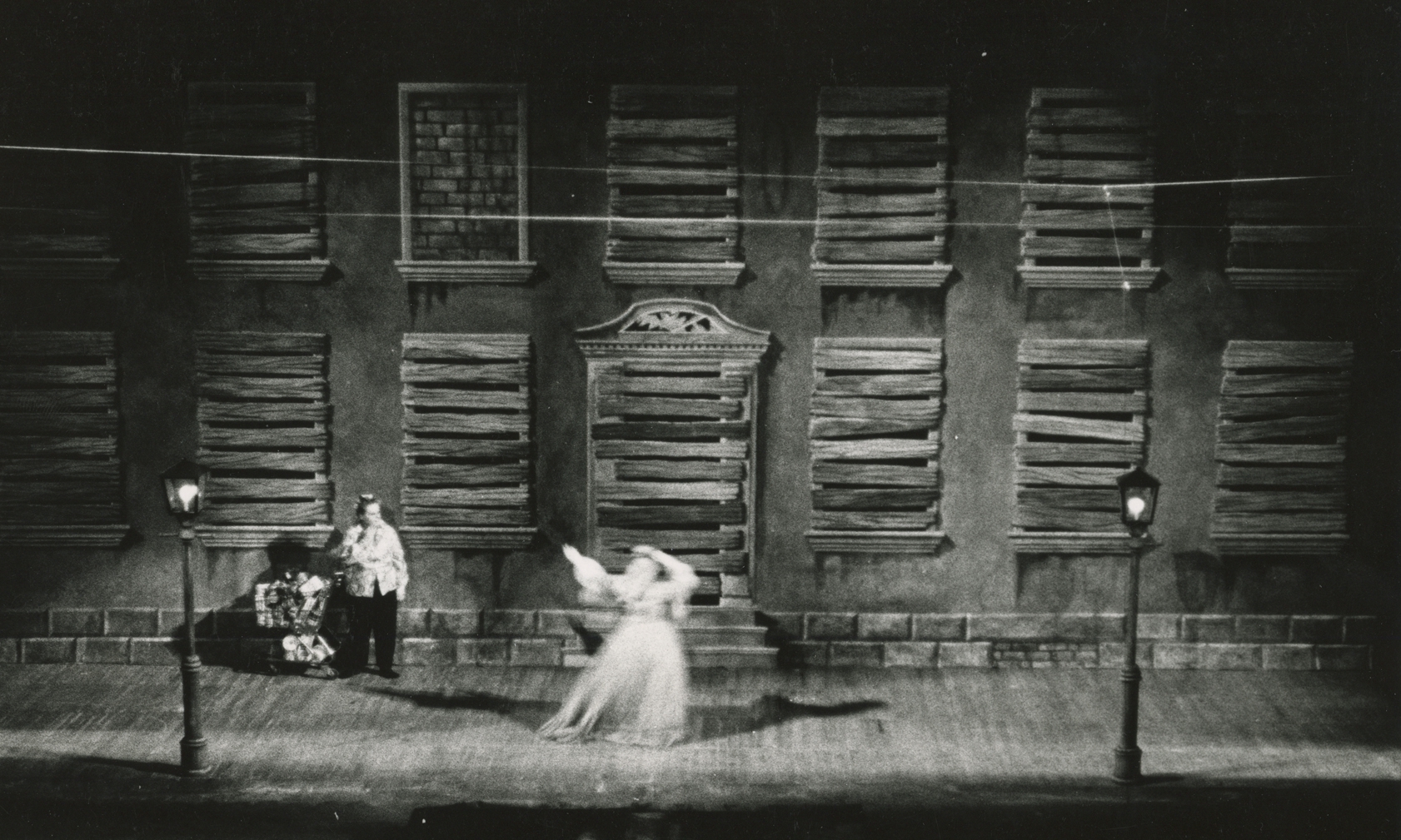

The work is a kind of retrospective of what Wilson and his Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds have done to date. The first four acts, lasting from 7 p.m. until around 2 a.m., have been seen here before as parts of ‘The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud’ (1969) and ‘Deafman Glance’ (1970). Close followers of the work can compare these with the earlier versions. The basic mode is enormous, elaborate, slowly moving tableaux vivants, big set pieces in which all kinds of often incongruous elements interact. The acts and their various prologues and inner scenes are like giant living paintings with sound, with huge backdrops in painted perspective and fantastic and elaborate costumes. Wilson revives all the scenic conventions of old-fashioned theatre, as well as inventing conventions of his own, always making their concreteness consciously felt.

But here I go generalizing, and this is an art of the relentlessly particular….

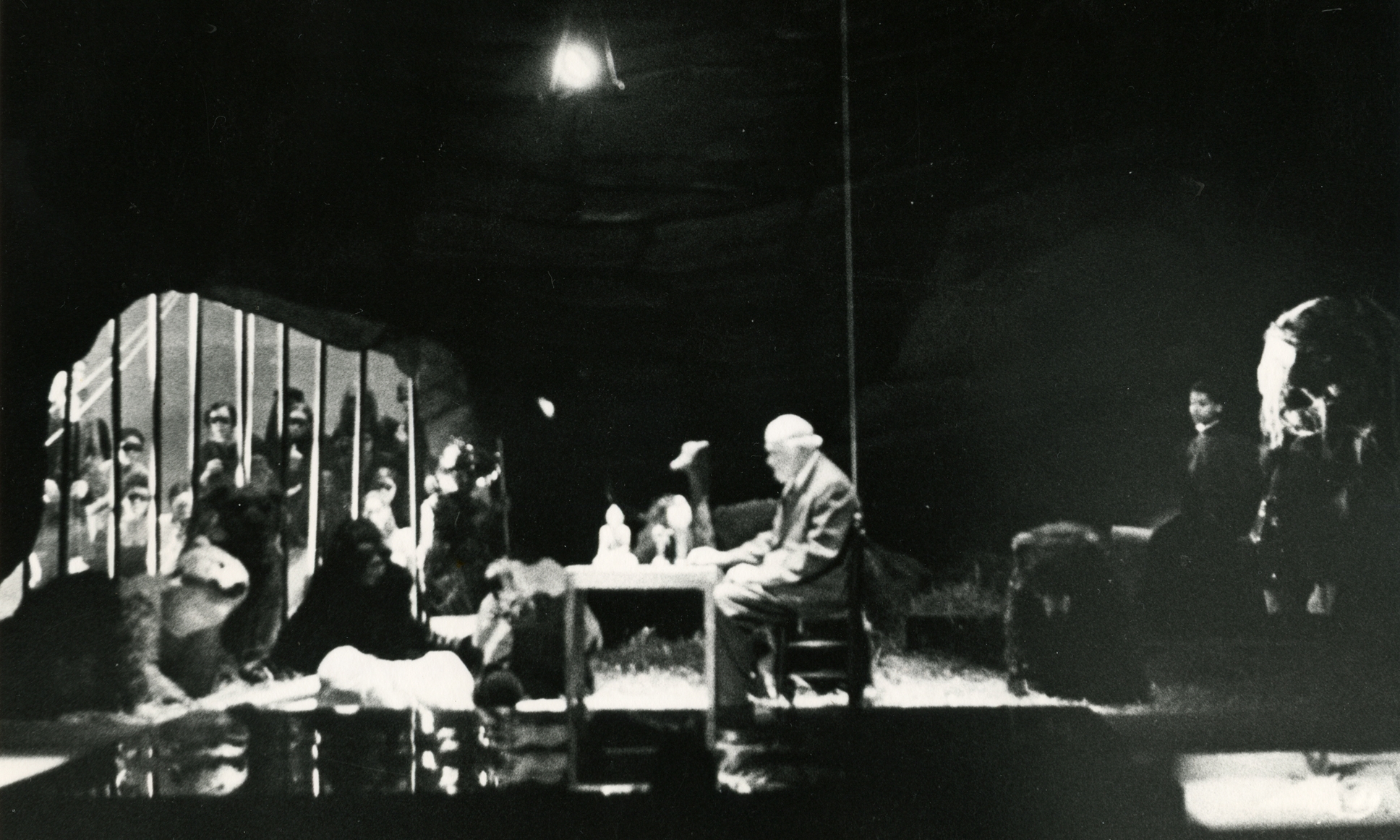

[The] eccentric, apparently arbitrary ‘art’ elements [serve] to hold it all together, to reinforce the sense of something more, and to enrich the texture. A runner in red runs across the stage every few minutes almost the whole night. Even more abstractly, a bunch of chrome hoops strung high above the audience are periodically moved slightly with a long pole. There is always so much going on that even at the long night’s deliberate pace the eye never catches up with it. Some of it is always changing, some of it always stays the same. You get interested in watching something on the left side of the stage—a giant turtle, maybe—and when you look back over on the right, everything is different. Or a new backdrop will suddenly slowly fly in and the whole reality be changed….

I went out to dinner during the third act but I remember how incredibly beautiful the cave scene was in ‘Sigmund Freud.’ Later I regretted having missed even a minute.

When I came back Medea had apparently just murdered her children and their bodies were being carried out by Joseph Stalin. The forest scene, Act IV, which is apparently the whole of ‘Deafman’s Glance,’ is extraordinarily beautiful, strange, and long, lasting a good three hours and tripping everybody right out.

Wilson’s work doesn’t have the loose focus of oriental all-night theatres…. I expected to be uncomfortable, but I wasn’t. It seemed quite natural to sit in a theatre all night. (But I hope this doesn’t start a trend: the next day is wiped out.) In fact, amazingly, my attention was held throughout. Once my normal bedtime had passed, I gave in to it and liked it more and more….

[By the fourth act] I was drawing conclusions, thinking the work was getting simpler and overcoming its tendency to morbidness. But the last and latest act is imagistically and formally as intricate as anything Wilson has done and by the end grew somewhat grating, maybe on purpose….

What is performed and witnessed doesn’t translate into anything. I often knew, even when I was paying close attention, that I wasn’t actually “following.” I didn’t know what to follow; I didn’t know if there was anything to follow. I didn’t even try to make sense of it. It’s in another language, one that has its meaning on another level than this one I’m playing with at the moment. It’s a slow, heady language, its content accumulated through years of work and elusive as any esoteric communication. In a sense it is a projection of Wilson’s head. But it deliberately goes beyond that, calling itself a school, initiating devotees, reaching back to a deeper level of theatre. What Wilson is making is mysteries.”